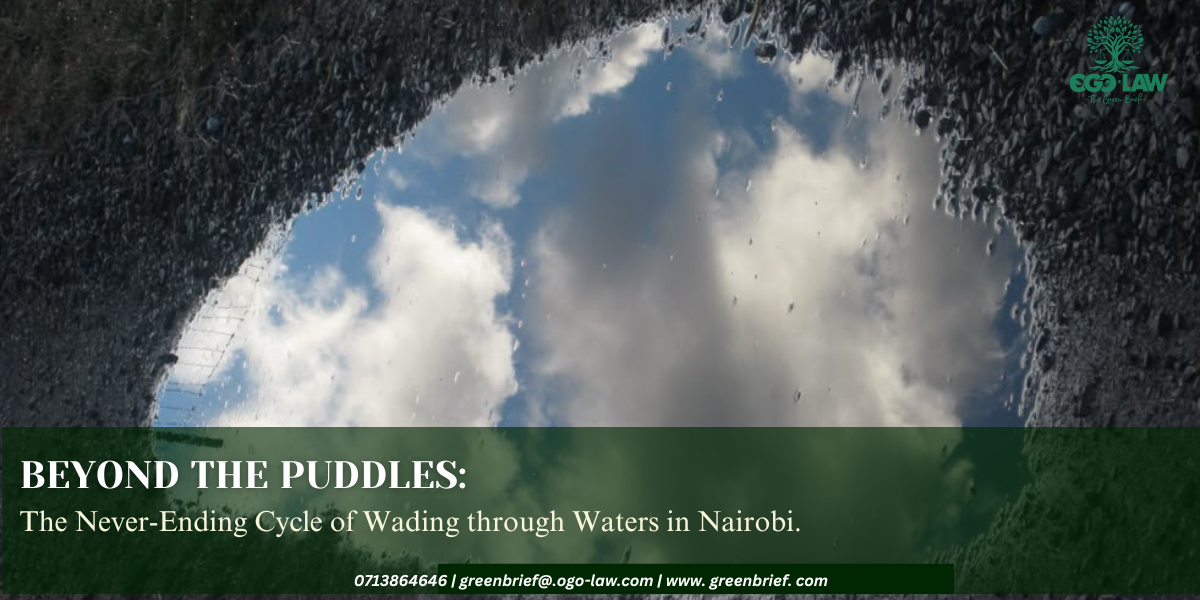

The recent rains experienced last week and early this week across the country have exposed the country’s incapacity on matters disaster preparedness. What a troubling paradox: a country that desperately needs water for agriculture and domestic use becomes paralyzed when that same water arrives in abundance. Every Nairobian dreads the CBD streets during heavy downpours because that is when extortionists are hard at work in terms of fare hikes, umbrella merchants, and mkokoteni handlers (the Nairobi boats). The impassable Mombasa Road is a story for another day; the pattern is always predictable yet implementation seems like a far-fetched mitigation strategy.

Kenya’s urban planning sector is a hub of ingrained failures and misplaced priorities which operates on a dangerous assumption that heavy rains are exceptional events rather than seasonal inevitabilities. The dilapidating drainage systems in parklands date as far as the 1990s and has been taken over by the mushrooming skyhigh apartments. Drainage systems designed for moderate precipitation buckle under intense downpours, while informal settlements built in floodplains bear the brunt of inadequate planning. The result is a cascade of failures: blocked roads disrupting supply chains, waterlogged hospitals struggling to serve patients, and schools forced to close when accessibility becomes impossible.

The rainy seasons come with lots of expenses on the taxpayers’ monies in compensation and emergency relief. Many people lose their properties and businesses due to flooding and impassable roads, crops are destroyed, with the tourism sector bearing a greater loss. Not to quantify the intensity of losses but tourism ranks as one of the top revenue streams for the kenyan economy. The irony is stark – the very rains that could boost agricultural output instead trigger economic disruption due to systemic unpreparedness.

Pro-active disaster preparedness demands a shift from reactive emergency to robust mitigation and adaptation strategies in terms of infrastructural development, capacity building and implementation of sound urban planning. This means upgrading drainage systems, enforcing building codes in flood-prone areas, and developing early warning systems that translate meteorological data into actionable community alerts. Countries like the Netherlands demonstrate that living with water requires engineering solutions that work with natural systems rather than against them.

The recent rains call for deliberation among various stakeholders to bury this recurring event for good.